Linear Regression with scikit-learn

What Is Linear Regression?

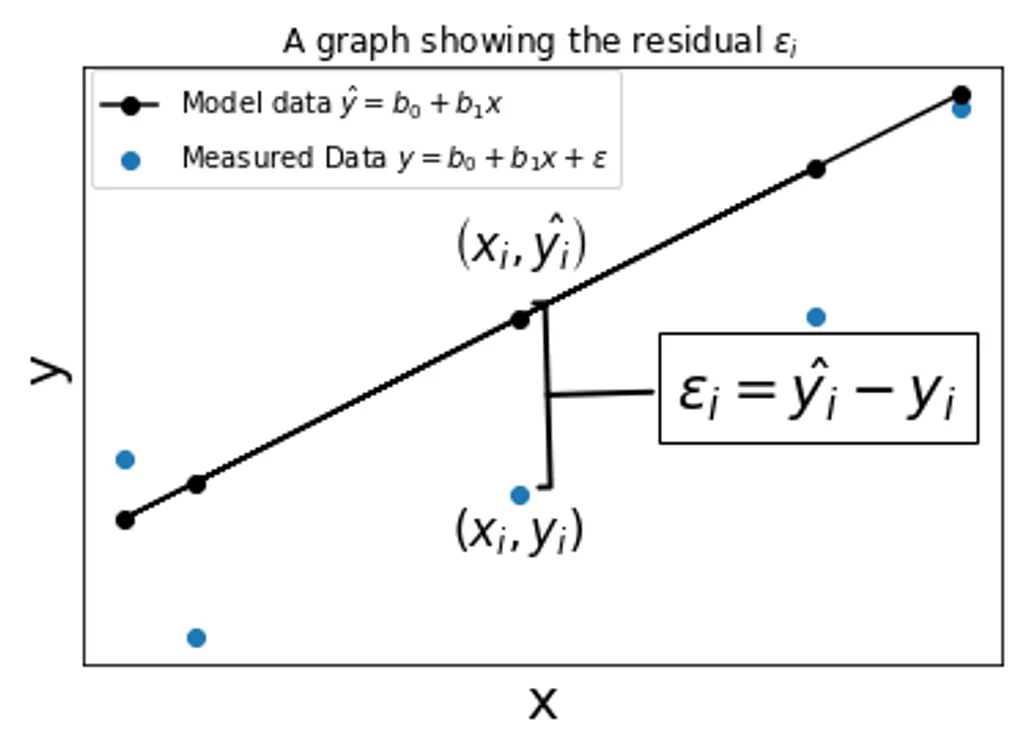

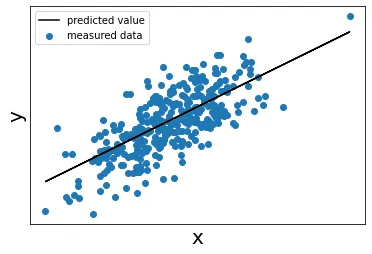

Imagine we had some data points like the plot below. The blue represents the data we measured and recorded, and the black line indicates a hypothetical line that best represents the data.

Why do we want to find this line? Well, if we knew the equation for a line that ran right in the middle of our data, predict any value using the equation of such a line with reasonable accuracy.

from sklearn.datasets import make_regression

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from sklearn import linear_model

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Generate regression dataset

X, y = make_regression(n_samples=1000, n_features=1, noise=35, random_state=1)

# split data/targets into test/train

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.33, random_state=42)

# Create linear regression object

regr = linear_model.LinearRegression()

# Train the model using the training sets

regr.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Make predictions using the testing set

y_pred = regr.predict(X_test)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.scatter(X_test, y_test)

ax.plot(X_test, y_pred, color='black')

ax.legend(['predicted value','measured data'])

# for major ticks

ax.set_xticks([])

# for minor ticks

ax.set_xticks([], minor=True)

# for major ticks

ax.set_yticks([])

# for minor ticks

ax.set_yticks([], minor=True)

ax.set_xlabel('x', fontsize=20)

ax.set_ylabel('y', fontsize=20)

A simple Linear Regression model takes the form below

where:

- is our response variable, i.e. the dependant variable, the value we are trying to predict

- is the regressor variable, i.e. the independant variable. It is assumed to be measured with neglible error.

- is a random error term that we cannot directly measure, however we assume it exists an accounts for any inacuraccies in our model

- is the bias, i.e. the y intercept of the linear regression line

- is the slope of the regression line

and are the values we are trying to find in a Simple Regression model, and they are assumed to be constant values and not functions of , which makes the equation linear.

The random error term has expected value (mean) of zero, and constant variance.

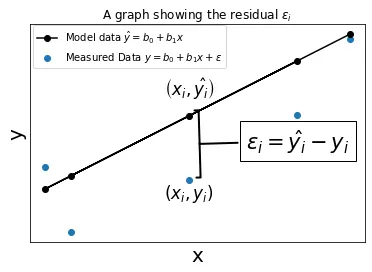

How does it work? Based on our assumed model, there is some error corresponding to each data point. This extra error is called the residual.

# Generate regression dataset

X, y = make_regression(n_samples=15, n_features=1, noise=20, random_state=5)

# split data/targets into test/train

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.33, random_state=42)

# Create linear regression object

regr = linear_model.LinearRegression()

# Train the model using the training sets

regr.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Make predictions using the testing set

y_pred = regr.predict(X_test)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.set_title('A graph showing the residual $\epsilon_i$')

ax.scatter(X_test, y_test)

ax.plot(X_test, y_pred, color='black', marker='o')

ax.legend([r'Model data $\hat{y}=b_0 + b_1 x$', r'Measured Data $y=b_0 + b_1 x + \epsilon$'], bbox_to_anchor=(0.6,1.02))

fs = 14

ax.annotate('$\epsilon_i = \hat{y_i} - y_i$', xy=(0.5, 0.45), xytext=(0.8, 0.4), xycoords='axes fraction',

fontsize=fs*1.5, ha='center', va='bottom', rotation=0,

bbox=dict(boxstyle='square', fc='white'),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='-[, widthB=1.6, lengthB=0.2', lw=2.0))

ax.annotate(r'$\left( x_i, \hat{y_i} \right)$', xy=(0.4, 0.68), xycoords='axes fraction', fontsize=fs*1.2)

ax.annotate(r'$\left( x_i, y_i \right)$', xy=(0.4, 0.2), xycoords='axes fraction', fontsize=fs*1.2)

# for major ticks

ax.set_xticks([])

# for minor ticks

ax.set_xticks([], minor=True)

# for major ticks

ax.set_yticks([])

# for minor ticks

ax.set_yticks([], minor=True)

ax.set_xlabel('x', fontsize=20)

ax.set_ylabel('y', fontsize=20)

We wish to make the sum total of the error for all of the data points as small as possible. In other words, we are minimizing the residual.

One method is to square the sum of the residuals, since having a negative value is undesirable as it instead subtracts from the total amount of error, which can be misleading. We can right the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) like so.

If we have data points, the total squared error is

Minimizing this function with respect to b0b0 and b1b1 is the same as taking the partial derivatives with respect to each and setting them each to zero. This results in two equations with two unkowns (once you sum over all the x and y values). The two equations is referred to as the Normal Equations.

These equations can be expressed as:

Example:

import numpy as np

# Generate regression dataset

x, y = make_regression(n_samples=1000, n_features=1, noise=35, random_state=1)

# Create linear regression object

regr = linear_model.LinearRegression()

# Train the model using the training sets

regr.fit(x,y)

x = x.reshape((1000,))

n = len(x)

s_x = sum(x)

s_xx = sum(x*x)

s_y = sum(y)

s_xy = sum(x*y)

print('n = {}'.format(n))

print('s_x = {0:.{1}f}'.format(s_x, 4))

print('s_y = {0:.{1}f}'.format(s_y, 4))

print('s_xx = {0:.{1}f}'.format(s_xx, 4))

print('s_xy = {0:.{1}f}'.format(s_xy, 4))- n = 1000

- s_x = 38.8125

- s_y = 2488.7840

- s_xx = 963.8755

- s_xy = 36596.1745

The equations reduce down to:

Even though it is a linear system with only two equations. Numpy can solve it for us.

A = np.array([[n, s_x],[-s_x, s_xx]])

b = np.array([s_y, s_xy])

v = np.linalg.solve(A,b)

# We get approximately the same results

print("solution by solving linear system")

print("b_0 = {}".format(v[0]))

print("b_1 = {}".format(v[1]))

print()

print("solution using scikit-learn")

print("b_0 = {}".format(regr.intercept_))

print("b_1= {}".format(regr.coef_))solution by solving linear system

- b_0 = 1.0135779148091075

- b_1 = 38.00855317991723

solution using scikit-learn

- b_0 = 1.0167510469725556

- b_1 = 37.92679771

We get aproximately the same solutions.

Conclusion

We are not quite done yet. Because is a random stochastic term meant to represent error in our measurements, it will not be the same each time we collect our data. This means the , our predicted value, will change each time as well. This in turn means our , values will be different each time as well.

In other words, each time we collect our data, due to random errors in the measurements, we would need a completely different regression line to represent the new values.

How to get around this? Well what we can do is essentially find the average values of and as we take more and more measurements. This will give us a more accurate fit.